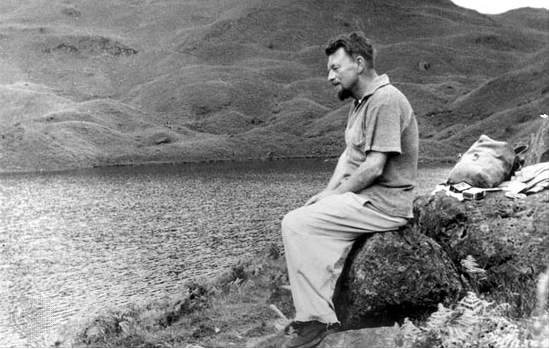

Malcolm Lowry’s 'Under The Volcano' (1947).

Malcolm Lowry’s cult novel portrays Geoffrey Firmin, an ex-Consul living in Mexico who slowly drowns himself in alcohol – thus consciously committing slow suicide – and yet who is unexpectedly killed under unforeseen circumstances.

All the themes of the novel are universal: life and death, love and hatred, joy and sadness, self-determination and fate, man’s littleness and the Universe’s immensity...

Yet, all ‘universal’ novels are not good novels.

What makes the difference here is that the novel works, it creates a powerful reality. Blending a drunkard’s visions with ethylic sarcasms expressed in free reported speech interspersed with Spanish sentences and quotations from Dante’s 'Inferno', Malcolm Lowry also makes perfect use of time and space in order to achieve maximum effectiveness.

TIME

'Under the Volcano' is a one-day novel such as Joyce’s 'Ulysses' or Virginia Woolf’s 'Mrs Dalloway': the Consul’s story takes place in twelve hours, from 7am (in chapter 2, as Yvonne arrives in Quauhnahuac, there is a “seven o’clock morning sunlight”) to 7 pm (in chapter 12, when the Consul is shot by the Chief of Rostrums, “the clock outside quickly chimed seven times”).

The novel itself (not the Consul’s story) lasts a whole year: in the first chapter, we meet Jacques Laruelle and Dr Vigil one year after the actual events. Laruelle recalls the Consul’s death which is the story we are going to read.

These two parts (i.e. the novel as a whole and the story of the Consul) are linked by the repeating of the sentence “a bell spoke out: ‘dolente…dolore’”, and by the fact that Laruelle is reminded of the Consul’s story because it had taken place on the same day of November, the Day of the Dead, of probable pre-Colombian origin, a very important holyday in Mexico. Families picnic in cemeteries, decorate the graves of their loved ones, children play with skeletons made of chocolate and even people dress up as skeletons.

This choice allows Lowry to use the event (Laruelle, as Mexicans do, recalls ‘his’ dead, the Consul). It dramatizes the Consul’s fate, packed into twelve hours, creates a larger-than-life dimension, and conveys a strongly expressionistic vision of fate - there are ‘signs’ everywhere - and death.

UNDER THE VOLCANO: AN 'ETERNAL' NOVEL

The Consul’s story never ends: once we get to the end, we actually get to the beginning of the novel when Laruelle remembers what we have just read. It is symbolized within the novel by the Ferris wheel of the fair: “Over the town, in the dark tempestuous night, backwards revolved the luminous wheel”).

This particular use of time, Lowry said, is “essentially trochal…the form of it as a wheel so that, when you get to the end…you should want to turn back to the beginning again” (Selected Letters, 88, cited in Sherill E. Grace’s 'The Voyage That Never Ends, Malcolm Lowry’s Fiction', Vancouver: U. of British Columbia Press, 1982).

This feature of Lowry’s novel is important: the cyclic time represented as a wheel is a reminder of Aztec religion (cf. Jacques Soustelle’s 'Les Quatre Soleils', Paris: Plon, 1967) and fits perfectly with the Consul’s obsession with black magic and cabalistic signs.

Within this cyclic and ‘horizontal’ representation of time, within the year and the twelve-hour time span of the novel, Lowry introduced deep ‘vertical’ incursions into the main characters’ past: the Consul’s life is recalled by his friend Laruelle whom he met as a teenager (chapter 1), whereas Hugh’s and Yvonne’s are respectively exposed in chapter 5 and 9.

This is meant to present the roles of the other dramatis personae (just as in any ‘classic’ novel) but also to draw their respective psychological features and their importance in Geoffrey’s life and as ‘counterpoints characters’ to Geoffrey’s – Yvonne and Hugh follow the same desperate pattern as Geoffrey. It puts emphasis on the metaphysical dimension of the novel: this is mankind’s destiny.

Another important fact in relation to the use of time in 'Under the Volcano' is that the story takes place in November 1938 (whereas Laruelle ‘dreams’ the Consul’s tragic end in 1939), a few months before the beginning of World War II. This element gives yet another oppressive climate to the story, as if through the lives of the characters we should feel the world in a state of decay, falling into chaos, as though we should understand the causes for the oncoming war.

'Under the Volcano' describes a world on the verge of collapsing, of committing suicide – just as the Consul is.

PLACE

Lowry intentionally named his novel 'Under the Volcano' and situated the action in a country where, according to Aztec mythology, two legendary volcanoes, the male Popocatepetl and his “wife” the female Ixcctacíuatl, eternally watch over mankind, and are strong symbols of the precariousness of life as well as of the impending death of simple humans.

He also deliberately chose to place his characters in Quaunahuac, the Aztec name of contemporary Cuernavaca, because the name conveys a strong ‘Aztec’ motif, with all its connotations.

Volcanoes symbolize hidden forces bubbling beneath the surface, threatening to destroy everything: “Under the volcano! It was not for nothing the ancients had placed Tartarus under Mount Etna, nor, within it, the monster Typhoeus, with his hundred heads and – relatively – fearful eyes and voices.”

The choice of Mexico was also very convenient for Lowry, for he had to ‘kill’ the Consul: Mexico with its history (“so far from God, so close to the United States”), its Revolution, its complex politics, its traditional violence and its poverty was the ideal place to get the Consul into trouble - as Lowry himself had been while in Mexico - and especially to create the Consul’s ironical end, a man who consciously destroys himself with alcohol and yet gets killed under totally unexpected circumstances.

Malcolm Lowry knew Mexico from a somewhat unlucky sojourn. In a letter of 2 January 1946 to his English publisher, Jonathan Cape, who had discussed the choice of that particular country for the novel, he wrote:

The scene is Mexico, the meeting place, according to some, of mankind itself, pyre of Bierce and springboard of Hart Crane, the age-old arena of racial and political conflicts of every nature, and where a colourful native people of genious have a religion that we can roughly describe as one of death, so that it is a good place, at least as good as Lancashire or Yorkshire, to set our drama of a man’s struggle between the power of darkness and light. Its geographical remoteness from us, as well as the closeness of its problems to our own, will assist the tragedy each in its own way. We can see it as the world itself, or the Garden of Eden, or both at once. Or we can see it as a kind of timeless symbol of the world on which we can place the Garden of Eden, the Tower of Babel and indeed anything else we please. It is paradisiacal; it is unquestionably infernal.

(Cited in George Woodcock’s article 'The Own Place Of The Mind: An Essay in Lowrian Topography', in Anne Smith’s 'The Art Of Malcolm Lowry', London: Vision Press Limited, 1978).

Mexico, with its history, its Catholicism mixed with pre-Columbian rituals – such as the Day of the Dead – , its landscape, its climate and its people, is both a ‘scenic’ country and a perfect setting for the Consul’s dark destiny:

- the Aztec ruins invariably recall human sacrifices

- the allusion to Emperor Maximilien’s execution in the palace he had erected and the following desperation and insanity of his wife Charlotte is a strong mirror of the Consul’s destiny

- Mexico’s fauna is a reservoir of symbols, such as the scorpios the Consul sees (doubles of himself as they are famous for their suicidal behaviour), or the vultures, an omen of death

- its flora is constantly mentioned because of the Consul’s addiction to mezcal, a strong alcohol derived from the leaves of cactuses, a nourishing plant yet a symbol of unbearable heat and desolate landscape

- its hot weather, its sun, are felt deeply by the reader and emphasize the oppressive climate of the book, conveying Judaeo-Christian visions of an omnipresent punishing God as well as terrifying images of the Sun God the Aztecs had to ‘feed’ with human blood lest it should die, thus emphasizing the inescapable fate of the doomed Consul.

Mexico’s national language equally plays an important role in the novel by underlining the Consul’s utter isolation in a foreign country. Sinister anathemas in Spanish are mixed up with the recurring “dolente…dolore!” leitmotif, an quote of the inscription on the Inferno’s door in Dante’s 'Divine Comedy' :

Per me si va nella città dolente

Per me si va nell’eterno dolore

Per me si va tra la perduta gente

Geoffrey Firmin is doomed, he is meant to die soon and is already entering Hell.

Time and space in Under The Volcano play a major role in its powerful beauty: by using them in his own personal way, Lowry achieved a very symbolic and expressionist world.

If the novel still stands out as a cult book and a major novel of the twentieth century it is in great part due to its ingenious use of time – precise yet ‘timeless’ – and to Mexico and the Day of the Dead.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Sherill E. Grace, 'The Voyage That Never Ends: Malcolm Lowry’s Fiction', Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 1982.

George Woodcock, 'The Own Place Of The Mind: An Essay In Lowrian Topography', in Anne Smith’s 'The Art Of Malcolm Lowry', London, Vision Press Limited, 1978.

©Sergio Belluz, 2017

A découvrir aussi

- The Owl and the Nightingale (circa 1210) - original text in Middle English.

- The Owl And The Nightingale (circa 1210): a comparative critical approach.

- Vampires, sorrows and sophisticated ennui: the cultural side of tuberculosis.

Inscrivez-vous au blog

Soyez prévenu par email des prochaines mises à jour

Rejoignez les 110 autres membres